Helping those who need it most

by Todd Julian

Today was a good day for a deserving family I represented in a personal injury matter. The mother and her eight-year-old daughter were involved in a collision caused by another driver who only carried the minimum insurance limits of $15,000 per person. The child suffered a severe Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), and after 19 days in Phoenix Children’s Hospital, her medical bills were more than $225,000. Under the circumstances, the parents could not imagine that hiring a lawyer would help and their daughter would ever receive anything by way of settlement. But we ultimately succeeded in recovering $215,000 from various insurance coverages, and after we negotiated the medical liens and cut our fees, there was a sizeable net recovery used to purchase an annuity that will benefit the child for many years to come. And there’s more—although a parent usually is not entitled to recover damages for the injury to a child, we convinced the insurance carriers to pay their policy limits of more than $100,000. Mom wept tears of joy when I called her today to tell her the news. Being a trial lawyer means helping those in need, especially when it seems that there is no hope.

Todd Julian, Certified Specialist in Personal Injury and Wrongful Death Litigation.

That’s Not My Dog! Who is liable for Injuries Caused by Dogs?

by Todd Julian

Under Arizona law, the owner of a dog is strictly liable for dog bites or injuries caused by a dog at large, but sometimes the question is who is the owner?

In this context, the courts use the term “statutory owner“ to determine who is legally liable, which comes from the statute which defines owner as anyone “keeping” an animal for more than six consecutive days. This definition seems clear enough, but as often is the case, there are many nuances. For example, I handled a case recently where the homeowner’s girlfriend adopted a dog and brought it home. The dog bit a guest, and the homeowner denied liability claiming it was not his dog. But the evidence showed that the girlfriend lived in the home at least part of the time, and the dog was kept there, such that the homeowner at least shared some of the responsibilities for caring for the dog, making him a statutory owner liable for the injuries. By contrast, in the case of Spirlong v. Browne, the Court of Appeals determined that a landlord who rented a room to the dog owners did not become a statutory owner and was not liable for the dog bite because the landlord did not actually exercise any care, custody or control of the dog.

Now, harkening back to the classic line from the Pink Panther movie where inspector Clouseau says to the hotel clerk “I thought you said your dog doesn’t bite,“ and the clerk responds with a shr style="margin: 60px 0 20px;"ug, “but this is not my dog.“ Then again, whether he is the statutory owner may be another question.

What’s the Difference Between a Large Dog and a Dog at Large?

by Todd Julian

In Arizona, an owner of a dog is strictly liable if their dog bites someone without provocation, or for injuries or damages caused by a dog “at large.” The statute defines “at large” as meaning a dog that is either not on a leash less than 6 feet long or otherwise “confined within an enclosure” on the owner’s property. But what does this mean in a practical sense?

The leash law is pretty straightforward, at least if you keep a grip on the expandable leash, but what about a dog that is inside your home or “confined” in your backyard? The term “enclosure” is not defined in the dog at large statute itself, but in other contexts it has been interpreted to mean a separate enclosure on the property, such as a crate or dog kennel. This means that if a dog is running free in the house or yard and knocks someone to the ground, for example, the owner of the dog is strictly liable for any injuries.

By way of illustration, I represented a young man who was riding his horse past a neighbor’s house in Cave Creek when a dog ran across the yard, spooked the horse, and the rider was thr style="margin: 60px 0 20px;"own off and suffered a compression spinal fracture. In this case the rider was not even on the property, and it was not clear whether the dog had jumped thr style="margin: 60px 0 20px;"ough the split rail fence before the horse bucked, but it did not matter because the dog was, by definition, “at large”, even on the property, meaning the owner was strictly liable for the injuries.

The strict liability statutes are not intended to punish dog owners, but rather to protect people who are bitten or injured. In most cases the dog owner has no reason to expect that that their dog may bite someone, or that someone may get hurt if the dog knocks a guest to the ground, but especially when such accidents are typically covered by homeowners’ insurance, public policy supports compensation over litigation.

Does my car insurance apply if I’m not driving my car?

by Todd Julian

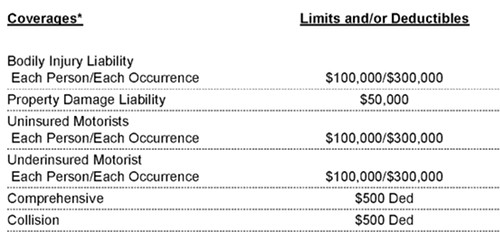

It does if you have Uninsured Motorists (UM) and/or Underinsured Motorists (UIM) coverage. Not only that, but UM/UIM coverage extends to members of your family at no additional cost. So dig out the Declarations Page of your auto policy and follow along with me.

Since 1972, car owners and drivers are required to carry liability insurance with minimum limits of 15/30/10, meaning that if you are liable for causing an accident, your insurance will pay up to $15,000 per person for the injuries of other people, up to a total of $30,000 per accident, and $10,000 for property damage, which usually means liability for the damage to the other driver’s car. The snapshot of the Dec Page above shows liability coverage of 100/300/50 with corresponding UM/UIM limits of 100/300. So don’t wait, find your policy or call your agent right now and confirm your liability limits--and make sure that you have UM/UIM coverage.

Since 1972, car owners and drivers are required to carry liability insurance with minimum limits of 15/30/10, meaning that if you are liable for causing an accident, your insurance will pay up to $15,000 per person for the injuries of other people, up to a total of $30,000 per accident, and $10,000 for property damage, which usually means liability for the damage to the other driver’s car. The snapshot of the Dec Page above shows liability coverage of 100/300/50 with corresponding UM/UIM limits of 100/300. So don’t wait, find your policy or call your agent right now and confirm your liability limits--and make sure that you have UM/UIM coverage.

If you’re at fault for causing an accident and you only have the minimum limits, that’s not much protection for you and your assets. But how do you protect yourself from the other guy who doesn’t have any liability insurance or only has the minimum limits? That’s where uninsured and underinsured motorists’ coverage comes in.

When you buy your car insurance, your carrier or the broker is obligated by law to at least offer UM/UIM coverage, yet many people still waive this coverage without realizing the value of the protection they get for a modest additional premium. Consider the alarming number of people who drive without any insurance, and that even a minimum limits liability policy of $15,000 probably would not cover your hospital bills nor would $10,000 cover the cost to repair or replace most vehicles. So, if the other driver doesn’t have any insurance, or not enough to cover your losses, then your UM or UIM applies, and by law your insurance company cannot raise your premiums for making a claim. Moreover, UM/UIM coverage is said to be “portable” meaning that you’re covered whether you’re a driver, a passenger or even as a pedestrian. As The Arizona Supreme Court noted in the 1985 case of Calvert v. Farmers Insurance Company: “The insured and family members insured are covered not only when occupying an insured vehicle, but also when in another vehicle, when on foot, when on a bicycle or when sitting on a porch.”

That’s right, even your family members typically qualify for the same coverage for any injuries arising out of a car accident that was someone else’s fault. So, check your policy and make sure for have UM/UIM coverage, and then you can relax on your porch and know that you’re covered.

“Hey honey, it says here that we’re both covered by my car insurance right now.”

Hedging Your Bets if You’re Injured at an Indian Casino

by Todd Julian

Most people don’t realize that when they step foot onto an Indian reservation or enter their Casino they are actually entering a ‘”sovereign nation” of that tribe, and they are subject to tribal law. Most importantly, all Federally-recognized Indian tribes have sovereign immunity, meaning that they cannot be sued for injuries or damages unless the tribe has expressly waived their immunity or Congress has passed a law specifically abrogating the immunity, which is almost unheard of in most cases. Even experienced trial lawyers often assume that Indian tribes and their business enterprises can be sued in Federal Court, but this is a mistake that will result in the case being dismissed and the lawyer being sued for malpractice. The truth is that you’re gambling with your legal rights when you’re visiting a casino, or any time you are on the reservation or doing business with an Indian tribe or entity, so it’s best to have a map of the minefield before you take your first step.

What is sovereign immunity and how does it affect my claim?

Tribal sovereign immunity not only protects the tribe from being sued, it bars suit against any wholly-owned tribal businesses or enterprise, such as casinos, ski resorts, gas stations or convenience stores and many recreational or tourist activities that take place on reservation lands. Exceptions to this rule of non-liability are almost non-existent, but can include some cases involving injuries caused by a tribal police officer or Indian health services provider or the rare case where a non-tribal entity is operating a business on the reservation. At least in Arizona, however, there is a narrow measure of protection for patrons who are injured at tribal casinos.

All tribes operating casinos in Arizona entered a Gaming Compact with the State, which is an “intergovernmental agreement” or treaty which includes the requirement that the tribes will purchase liability insurance and agree not to assert sovereign immunity to bar claims brought by injured casino patrons. The tribes were also required to adopt rules and procedures to be followed for legal claims. Unfortunately, each tribe’s Tort Claims Ordinance is different, and there is no consistency regarding the law or procedures to be followed. More often than not, the applicable tribal law is not available online, and the failure to follow the specific procedures and deadlines will preclude any claim or recovery for injuries.

What Law Applies?

Any claim or lawsuit against a tribal casino is actually a claim against the tribe itself, which means that it must be brought in tribal court and under that tribe’s law. In all cases there are deadlines to file a Notice of Claim or a lawsuit—some as short as 90 to 180 days—and any misstep is fatal to the case. One of the biggest challenges is to try to figure out the applicable law and rules of procedure for the particular tribe, especially because it is never posted on the casino’s website and more often than not it is virtually impossible to find from searching public records or on the internet. Here again, every tribe is different, as are the rules and the law to be followed.

In most circumstances a licensed attorney can pay a fee and be admitted to tribal court, although there are some tribes that require practitioners to pass a separate bar examination. One tribe, the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community, which operates Talking Stick and Casino Arizona, actually has a rule that prohibits licensed attorneys from appearing in tribal court—only non-lawyer tribal “advocates” are allowed in civil cases. In every case it is important to not only have a firm understanding of the tribal law and the procedures that are unique in each jurisdiction, but also the experience of litigating cases in tribal court. After all, when it comes to personal injury claims against tribal casinos, it’s always a gamble.